Analytics As Journalism

Analytics as a corporate function is exceptionally new. There’s no simple formula for success. How could there be? It would be obsolete within mere years, even if it existed.

But there is one framework that I keep returning to, that’s been useful so much more than not: analytics as journalism. Here’s how.

The story is the story, the process is Boring

Open with a headline. Follow with a lede sentence. Then given me the who/what/where/when/why to close out the first paragraph. Flesh out details, quotes, sources, and context on the story in the following paragraphs. This is the structure of a piece of news, and we would do well in analytics to copy it.

Why? Well think of the last time you read a news article that opened with, “we waited outside the source’s house and then called back and was referred through their secretary until we finally found out the news about the senator’s position, which was…” Never. They open with, “Senator X’s position is…” And yet, how often do we in analytics begin our presentations with “I went out to see if there was a causal relationship between X and Y, so I did a regression and instrumental …”? Far too often.

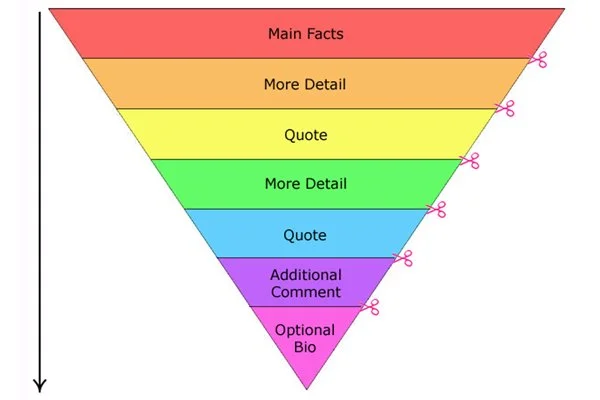

In journalism, they call this the “inverted pyramid.” Every sentence should be in decreasing order of relevance. Why? Because when you write an analytics post, or give a presentation, you might lose 90% of your audience 10% of the way through. So why not make sure those folks get what they need?

Finally, this structure allows the reader to control their own signal-to-noise ratio. When I read a news article about stock movements, I read one paragraph. I’m good. When I read a review of the latest Nic Cage film, I read every paragraph. Giving the reader control over their own signal to noise ensures that they will come back for more.

Scoops, News, Drip, and features

Some Data Scientists focus on the big meaty analytics-as-a-game-changer work. “We’re losing our marginal users, here’s 17 reasons why and how to solve it over the next 2 years.” These are great - don’t get me wrong. But treat them like “features.” Big multi-page investigative reports are wonderful parts of journalism, but they’re also not the mainstay.

The mainstay is regular news. It’s Monday morning. Your CEO has grabbed a cup of coffee, and locks into work. What do they want? In tech, in the modern world, a lot of them want data. They want to load up a dashboard and look at how many people are using their product, if anything happened over the weekend, if there’s a fire, or a big jump somewhere. This is the regular news. Make it a dashboard if you want, but make sure that you can fill the need.

But also, get the scoop for big events. Did your company launch a new feature last night? I guarantee leadership is hungry to see how it did - get there first. Too often I see data stacks built with a “we need 48 hours for the data to land” so the PMs just go to the engineers for some approximates instead. By the time Data Science feels comfortable to speak, they often find no one left to listen.

Finally, think about “drips.” I’ve often seen data scientists drop a huge 12-page thesis on how the business should change, never reference it again, and then ask why leadership didn’t move based on it. Journalists don’t do this, they drip. They drop an investigative piece. Then next week, a new angle on the same story. Then again, and again. You wouldn’t put a pizza in the oven for a minute and ask why it’s still frozen - and yet many in analytics don’t think of time as an ingredient in their output.

Elements of trust: Sources, retractions, facts and Opinion

Analytics is an influence function, which means we’re only ever as effective as we are trusted. There is nothing that will destroy productivity faster and more completely than someone thinking, “but is that datapoint really true?” This is the same for journalism - so how do they solve it?

The first is sources. A solid reporting framework will be founded on solid sources. Get multiple sources, whenever possible. Get them on the record, whenever possible. Get unbiased and potentially disagreeing viewpoints, whenever possible. The analogies for analytics is to make your work reproducible and transparent. Post links supporting all of your work. Make it one-click re-runnable. Note your caveats.

The second thing journalists do is retractions. There’s a fine art to being wrong in analytics, and I think the journalism model paints it well. First of all - your team will be wrong at some point. The only way to avoid it is to never report anything. So what do you do? I like three rules:

1. Be first. People are very forgiving to you saying “hey I noticed I got this wrong,” but if someone else finds an issue first, they’re left wondering if they might find more. The only caveat here is that you should only be first if you know you won’t need a second retraction - so make sure you’ve got the right data this time.

2. Be anti-fragile. The best teams don’t just fix mistakes, they put mistakes to work. What does that mean exactly? Find every system that broke that allowed the error to occur, and write a scaled solution so that no errors of that class can ever recur. Did a pipeline fail and you missed a dependency? Don’t just fix the dependency, write tests for all your pipelines. Was the methodology not vetted enough? Get the team to peer review. Mistakes are the fuel for a better system, use it.

3. Get messy. Retractions in analytics can get messy. Imagine you reported a number to the C-Suite, and they’ve already started making plans based on it. You are not going to want to go in and fix that - but you have to. If you do it maturely and carefully, and take responsibility, people will end up respecting you more. If you watch a mess occur because the data was bad, and they find out, people will shut analytics out of the process.

And the last journalist trick for trust: separate fact from opinion. Journalists do this with literal fact and opinion sections - which is sometimes useful. I’ve seen successful teams have a “fact-only” space and an “opinion-only” space. But the meta-lesson is what’s crucial: If you find that there is a controversial insight, and people are arguing about the facts, then you are not yet ready for opinions. If you find yourself here, back up, set out the facts as the data presents it - and get alignment. Only after everyone has agreed that the facts are not in dispute can you move back to opinion.

Bonus Controversial Section: Speaking Truth to Power

There’s also another thing journalism does well, and analytics can sometimes do well: Speak truth to power. This is sometimes controversial, and I would say it works to better and worse degrees in different organizations. But here’s the basic theory:

Analytics has a special capacity within a company to balance narratives with data. Companies generate narratives as a matter of course. The company is founded on a mission. Individual leaders will bring their intuition to the mission. And teams form stories about how to execute. That’s the natural order of a functioning business. Analytics allows for an additional loop for this process - validation. E.g.:

1950’s company: “We believe there’s a market for widgets.” They build the widgets. People buy or don’t buy. The market validates, but slowly.

2020’s company: “We believe there’s a market for widgets.” Analytics does a market analysis, and validates quickly.

But there’s some trade-offs to be careful with. First, an analysis is only as good as the data you have, and you could very easily conclude that there’s no market for a car in a world with TAM only for faster horses (on the other hand, everyone wants to believe their widget is the Model T and not a Segway). Second, if you validate everything through data, you run the risk of atrophying the muscle of product lens thinking. And if that happens, your team can optimize but you can never really innovate. So consider this aspect carefully.